====

In 1985 the Toronto Film Festival (or the Toronto Festival of Festivals, as it was known then) planned a book publication in conjunction with its “10 to Watch” sidebar program featuring ten emerging directors. Alan Rudolph, fresh from the success of Choose Me, was selected as one of the featured filmmakers - but Toronto had difficulty finding a Rudolph partisan to write a 40-page monograph. Dave Kehr of the Chicago Reader happened to know that I admired Rudolph and recommended me, and I don’t believe I had any competition for the job. (The book was never published, but a greatly truncated version of the monograph appeared in the Toronto catalog.)

I had a chip on my shoulder about Rudolph back then. I wrote in the monograph, “That the achievements of Welcome to L.A. and Remember My Name were not greeted with widespread critical acclaim can be chalked up to taste; that they passed almost unnoticed comes close to discrediting American film criticism altogether.” I even took a little indirect swipe at my employers: “The Los Angeles Film Critics Association insulted Rudolph with its ‘New Generation’ award, almost a decade after the one-two combination of Welcome to L.A. and Remember My Name established him as one of the most important talents of the seventies.”

My distinct impression at the time was that Rudolph’s films were a hard sell, and that a lot of viewers were rubbed the wrong way in the 70s and 80s by his combination of expressionistic romanticism and amused detachment. “Welcome to L.A., the best known of Rudolph's films before Choose Me, is a risky subject for casual conversation, often stirring bitter memories of wasted admission fees for which we Rudolph defenders are somehow held accountable.” It’s difficult to document this antipathy now. My memory is that critics of the time tended to be modestly favorable on early Rudolph, though few or none were committed enough to keep the films in the public consciousness. Rudolph’s association with Robert Altman was front and center in most reviews, and critics usually discussed the films as emanations from the Altman universe.

Something may have changed since then. Young cinephiles no longer seem troubled by Rudolph’s films when they discover them - which still isn’t as easy as it might be, thanks to uneven distribution. Film internet buzz about Rudolph has been steady and affectionate for many years, and widespread enthusiasm greeted the recent Rudolph retrospective at the Quad Cinema in New York. Part of this improvement (assuming I’m reading the signs of change correctly) is surely due simply to the passage of time and the accumulation of individual films into a coherent career achievement. But I can’t help feeling that the zeitgeist has also shifted in a way that favors Rudolph. The year before Choose Me, Jim McBride’s remake of Breathless came out to near-universal scorn and dismissal. It shares a few qualities with Rudolph’s work: bright colors, an acceptance of overt artifice, lively rhythms, light-hearted detachment from a potentially serious story. It too is now widely if not universally respected. The 80s and 90s saw the rise of Hong Kong action cinema, then of Quentin Tarantino, both of which ratified a reflexive, pop approach to genre that Rudolph, in his own way, had accomplished years before. On the art-film circuit, Hal Hartley, who is to Godard as Rudolph is to Altman, accumulated a sizable fan base with a sensibility that overlaps Rudolph’s in a number of areas. My guess is that Rudolph’s films are not the only artifice-reliant, reflexive works of recent decades that would look better to today’s filmgoers than they did at the time. (For instance, I suspect that Claude Chabrol’s universally dismissed genre work for hire in the late 60s is due for reevaluation.)

Hanging out in the lobby of the Quad after last month’s Rudolph screenings, one could readily observe the surprise of young cinephiles that so distinctive a filmmaker, who bucks convention in so many different ways, would not have received greater acclaim. In the years since I wrote my monograph, my view of film authorship has shifted slightly: whereas once I tended to think of powerful filmmakers as master strategists who calculated their effects, I now tend to see their artistry as a collection of personal predilections expressed forcefully. Obviously both models are true at the same time, or can be...but the latter better explains the almost helpless consistency of the filmographies of so many important artists. In any case, as an afterword to my old monograph, here’s a little list of filmmaking decisions that Rudolph makes so often that they feel like urgencies.

A desire to expose the fiction as fiction

- Sometimes this desire is blatant: as when characters look directly at the camera at the end of scenes, a running practice in Welcome to L.A. that makes a comeback in Ray Meets Helen (via Andre, the boy who befriends Ray).

- Usually it’s subtler, as with the exaggerated use of coincidence and repetition. Choose Me took this tendency as far as it could go: the symmetry of the hookups is like a game the audience is invited to play. We see it again in Ray Meets Helen, with the same building as the residence or the focus of all five main characters.

- A similar tendency is the re-use of a small number of locations, with the same characters present each time we see the location: almost a commentary on making films with limited resources. There are many examples: Mr. Nudd’s drugstore in Remember My Name, Eve’s bar in Choose Me, the café in The Moderns, the bar near the staked-out ranch in Love at Large.

- Dialogue: characters often do the work of categorizing themselves. For instance, Tyra Ferrell’s morgue attendant in Equinox signals her ambition: “This story is going to raise me up out of the junk. People are going to want to sit next to me.” Similarly, Nolte underlines his character’s concept with his many references to finance in Investigating Sex. (Rudolph has this tendency in common with Hartley, by the way.)

- References to genre, and genre dialogue, are often so exaggerated that they are necessarily reflexive: the Fat Adolph story in Trouble (Bujold says, “If it was evil, he was into it”), the entire presentation of Anne Archer’s femme fatale in Love at Large.

- Characters who deviate from our expectations in order to collaborate in creating the film’s tone. A good example is John Hawkinson’s unpleasant cop in Ray Meets Helen, who quickly becomes a bit of a philosopher: “We’re all wearing masks.”

- A purification of gesture that resembles choreography: the violence of the passengers in the crowded bus in Equinox; or Tomei putting Modine’s hand on her breast in the same film. (This is another characteristic that Rudolph and Hartley share.)

- Music: of course there’s the obvious reflexivity of the studio musicians in Welcome to L.A., who are shown creating the soundtrack music. But there are also uses of music that are basically commentative, like the Hollywoodish music over the slapstick-y Emmet Walsh scenes in Equinox. And music that contradicts the scene’s tone in a jarring way, like the diegetic easy-listening music in the beauty salon in Mortal Thoughts that continues over the Headly-Willis fight and the poisoned coffee cup.

- Similarly, there are times in Rudolph when humor so disrupts the drama that one registers it as a form of direct address. The film I’m thinking of that best illustrates this extremity is Trouble in Mind, where a quite serious and emotional genre story increasingly shares the screen with a campy, obstreperous humor that one would expect to banish the initial gravity. (Though of course it doesn’t.)

- While speaking of Trouble, we might as well mention in passing the architectural models that Kris Kristofferson’s Hawk builds, which are introduced as characterization, pass through the stage of metaphor, and end as a bit of the production designer’s work placed within the diegesis.

Kinds of people he likes

Or puts in his films repeatedly, anyway.

- People who stand at an amused distance from their own crises. Keith Carradine’s Carroll Barber in Welcome to L.A. is the first and best example. I wrote, “Carroll Barber walks through the emotional wreckage of Rudolph's Los Angeles at a serene philosophical distance from his own pain, smoothing out the peaks and valleys of his psyche just as Rudolph levels the film's tone with his remote but sympathetic overview. A little ironic smile creeps across Carroll's face at the slightest observation, about either himself or others; his gestures are slow and measured, sometimes consciously overstressed, as if the observer within him is amused to see essence transformed into existence by any simple act.” Another good instance is Julie Christie in Afterglow, always half-smiling and looking in on her own sorrow.

- Transpose this detachment into a comic mode, and you get protagonists who become frustrated but manage to deal with it. Tom Berenger in Love at Large is forever perplexed at his encounters with difficult or unmanageable people: his girlfriend (Ann Magnuson), or a bizarre taxi driver. Carradine dealing with medical obstruction in Ray Meets Helen is a running joke - a rather dark one, but ultimately a demonstration of endurance; the bartender who must deal with drunken Samantha Mathis in the same movie shows the same spirit.

- Honest people. Some Rudolph characters are explicitly labeled as honest, and fulfill their missions: Carradine’s Mickey in Choose Me, Nolte’s Lucky in Afterglow make it a point not to lie. Even apart from the obvious examples, there really aren’t many lies in Rudolph at all, which is remarkable given his affection for farce: he seems to enjoy truthfulness. Even the few liars in his films, like Geraldine Chaplin’s Emily in Remember My Name, are so poker-faced and outrageous about their lies that they practically notarize the truth.

- Guys in Rudolph, sympathetic though they tend to be, are often comically afflicted with guyness. Jealousy and sex conflict abounds, from protagonists and antagonists alike: Patrick Bauchau in Choose Me, Keith Carradine in Trouble in Mind, The Moderns and Ray Meets Helen, John Light in Investigating Sex. Macho bluster often takes over an ordinarily balanced personality as a fight looms or subsides: Carradine sets the pattern in Choose Me (“I’m going to kill the son of a bitch”); Nolte and Jonny Lee Miller in Afterglow make a running gag of it. Carradine in Ray Meets Helen is a compendium of guy traits: instead of the expected pathos during his tale of woe, he tells young Andre “Chicks dig boxers”; his regained swagger as he tries to pick up Locke is cliché tough-guy stuff; and there’s a funny running gag of him fending off Sondra Locke’s introspection about death automatically. The most interesting variation on this theme is Hawk in Trouble in Mind: he is maladjusted and borderline criminal in the film’s first half, and Rudolph lets his ear for unregenerate masculinity write the character. Later Hawk reverts to a more typical level of testosterone for a Rudolph guy.

- People who don’t go gently into that good night. Emily in Remember My Name doesn’t submit to being dismissed or blown off, whether by the drugstore supervisor who grabs the cigarette from her mouth or by the bartender who takes her for a prostitute. Even with her lover/superintendent Pike, Emily maintains passive resistance in every conflict until she gets her way. Henry, the less assertive of the two versions of Matthew Modine in Equinox, seems maddened by his suckerhood and becomes increasingly determined to escape it. Modine here recalls Eddie Bracken in Preston Sturges’s films, and the pluck of Rudolph’s marginalized characters is not unlike Sturges’s. As in Sturges, supporting characters also tend to restore their dignity: in Equinox, there’s the beggar who walks away from an offer of money with a poker-faced “Good luck, mister,” and the lawyer’s daughter who is at first bested by Ferrell’s strategy but comes back with a modicum of power restored.

And then there’s a character type that deserves its own discussion:

The Rudolph crazy

- We get a number of variants on this type right off the bat in Welcome to L.A. The archetypal Rudolph crazy in the film is probably Sissy Spacek’s maid/prostitute, but Geraldine Chaplin’s Karen Hood, barely more in touch with reality, sends a strong pro-crazy signal by winning Carroll Barber’s romantic sweepstakes.

- And Rudolph isn’t even playing much with comic forms yet at this point. Chaplin takes craziness further in Remember My Name, suspending the entire film in a contemplation of her unpredictability; Choose Me, with its embrace of farce, cultivates a number of varieties of craziness, with Bujold’s Nancy Love the most certifiable. (Carradine puts the film under the sign of Crazy by escaping from an asylum at the beginning.) Marisa Tomei in Equinox is a memorable later variation on the theme.

- Of course craziness in life often has the same qualities as comedy does in fiction: displaced behavior, inappropriate repetition, etc. The Rudolph crazy helps make farce work without the lies that Rudolph generally prefers to avoid: characters whose emotions genuinely change in an unstable way are a workable basis for farce when imposture ploys are taken off the table. When Rudolph characters are only part crazy, it’s the part that serves this comic function (e.g., Mickey in Choose Me falling in love with every woman in the movie). The philosophical implication is that people don’t need artificial devices to have relationship problems.

- Many Rudolph characters who can’t quite be described as crazy nonetheless have much in common with the Rudolph crazy. Headly in Mortal Thoughts is one such character (recall that great moment when she nearly crashes the car, completely unfazed and chewing gum), and she still functions in the film as an effective threat; Chaplin in Remember My Name can be pretty scary at times too. Lori Singer in Trouble in Mind is basically an embodiment of romantic innocence, but her childlike demeanor and clumsiness puts us at a comic distance from her and suggests the unpredictability of the Rudolph crazy. Traveling in the opposite direction, Lara Flynn Boyle in Equinox starts out as a full-blown Rudolph crazy, but effortlessly transforms into an affecting embodiment of romantic longing.

Mystery

More than almost any other filmmaker, Rudolph seems to enjoy mystery for its own sake rather than a means.

- Simple inaccessibility: Carradine in Welcome to L.A. is the archetype, but Lauren Hutton in the same movie functions solely as an emblem of inscrutability. Carradine in the bathtub in Choose Me is a great, pure moment of mystery.

- Moments of mysterious pleasure: like Carradine’s sunny grin at what should be his worst moment in Welcome to L.A., when Chaplin reunites with her husband. There are many other such moments: Spacek in Welcome to L.A. taking money from Considine; Kaki Hunter’s knowing grin as she says “He’s so skinny” about Alice Cooper in Roadie.

- The impassive onlooker, the master of ceremonies: Cedric Scott, the producer, at the console in Welcome to L.A., flipping a quarter across his knuckles; Terrence Howard sitting behind the spinning bike wheel in Investigating Sex.

- Mystery of the image, images that contain barriers to looking: fuzzy TV images of Demi Moore in Mortal Thoughts; Carradine through the blurry windshield at the end of Trouble in Mind.

- Mysterious transformation: my favorite is Berry Berenson chain-smoking and talking tough at the end of Remember My Name; of course, there’s Carradine’s incongruous glam makeover over the course of Trouble in Mind.

- Unpredictability of behavior - which connects us back to the Rudolph crazy. A good example among many: the scene of Chaplin tearing up the flower garden in Remember My Name, an act rendered mysterious by slow, eccentric rhythms.

The pleasure of genre

- Genre sometimes functions as a wink: we aren’t supposed to feel the oppressiveness of film noir in Love at Large, for instance. Big performances and obvious borrowings have the effect of distancing us from genre here: Archer’s slinky voice, the close-ups of her lips talking on the phone. Sometimes a small dose of genre is a light-hearted or familiar pleasure to ward off heaviness: Hilly Blue’s henchmen in Trouble in Mind come to mind, maybe even the threatening car full of joyriding boys in Mortal Thoughts.

- Even in such cases, though, the wink is partial. Love at Large keeps genre play alive even as it gets serious, and puts the sincere love story into relation with the genre elements: e.g., Berenger’s rejection of Archer’s proposition: “It would be as thrilling as winning the exacta, but I’m in love with someone else.” Remember My Name uses comedy to distance us from the pain implicit in the genre story, but certainly doesn’t disown the pain; Equinox is wildly comic but basically delivers on all its genre expectations. Trouble in Mind is an unusual instance: a very serious genre story disrupted by a campy one, but not displaced by it - its ending is as full-bodied in its emotionality as genre gets.

- It’s worth noting here that Rudolph’s action scenes are consistently very good, often highly choreographed, somewhat conceptual, not much like the ambient action direction of the Avid generation. Endangered Species hinted at his flair for action, which burst forth in the three Carradine-Bauchau fight scenes in Choose Me, was further demonstrated in the Nolte-Miller brawls in Afterglow, and perhaps peaked with Dermot Mulroney’s one-sided fight with John Light in Investigating Sex. An interesting variation is Love at Large’s barroom brawl between Kevin O’Connor and Ted Levine, the action a backdrop to the revelations of the men’s conversation.

Less is not more

Rudolph is extra, not basic.

- Camera: the omnipresent camera moves seem like a first principle rather than a reaction to material. Give Rudolph a mirror or a TV monitor and he’ll use it to pan or track from one representation of reality to another - there are many examples; even the somewhat calmer camera in Ray Meets Helen hits those mirrors at every opportunity. The camera’s freedom pretty much excuses it from service to plot and genre, and this separation harmonizes well with the detached perspective and self-awareness that Rudolph cultivates in different ways.

- Gels, colored light: again, it feels as if he slaps the gels on first and asks questions later.

- Decor: generally pretty wild. Salient examples: the red apartment with blue painting in Afterglow; the smoked-out period ambience of The Moderns; the crazy nightclub and Hilly’s banquet in Trouble in Mind, which arrive at camp.

- The telephoto haze: a world of long lenses, tight frames, and compressed foreground-background perspective. It’s part of Rudolph’s link to Altman, and is usually coupled with aural omnipresence.

- Wildly exaggerated acting: Jennifer Jason Leigh in Mrs. Parker, Berenger in Love at Large, Considine in Trouble in Mind, nearly everyone in Breakfast of Champions and Roadie.

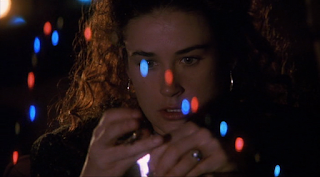

Rudolph’s effects are generally in the service of his romanticism - or perhaps it’s more capital-R Romanticism in its focus on subjective emotion. His work is a tapestry of larger-than-life effects that offer us pleasure and beauty. A few of the most vivid: the track-ins to devastated but smiling Carradine in Welcome to L.A.; Remember My Name’s decor-drenched drinking scene; the light coming up on Kristofferson’s face at the beginning of Trouble in Mind; phantom Neve Campbell haunting Dermot Mulroney’s onanistic reverie at the end of Investigating Sex. A detail that struck me as emblematic of Rudolph’s sensibility: at the most noir moment of Mortal Thoughts - which is pure film noir at the script level at least - Rudolph’s choice of expressionist effect is to reflect a string of brightly colored Christmas-y lights in Demi Moore’s windshield. I can’t think of another filmmaker who would give us that kind of direct pleasure at that particular point in that particular story.