Ever since widescreen TVs became fixtures in bars and cafes, we've been exposed to countless images that were intended to be displayed in 4:3 ratio but are stretched horizontally to fill a 16:9 screen. My informal survey reveals that nearly everyone would rather see an elongated image than deal with black space to the left and right of a properly projected 4:3 image. Something about wasted space bothers a lot of people.

I've been afraid for years now that the public would become acclimated to stretched images, and there's some evidence to support that fear. This weekend I watched a digital projection of Ryuichi Hiroki's Love on Sunday 2: Last Words at the IFC Center, as part of the New York Asian Film Festival. As near as I can figure, the tape was letterboxed, but the projectionist screened it 16:9 anyway. Anyway, the effect was much like all those widescreen TVs in bars that make everyone look like an endomorph. I ran out to the lobby twice to object, but the management didn't take me seriously, and I had to watch the film that way. I didn't see any other patrons complaining, so I guess they figured I was a lone nut.

So why don't these elongated images drive everyone crazy?

General discussion of films, and specific recommendations of films playing in the New York City area.

Monday, June 30, 2008

Saturday, June 28, 2008

Assorted Screenings in NYC, June-July 2008

There are a few interesting or rare items on the NYC film calendars in the next few weeks. I haven’t seen everything I’m about to mention, so consider this post a heads-up for the adventurous.

- Japanese director Naomi Kawase, who hasn’t had many NYC screenings, is getting some attention from Japan Society via its Japan Cuts series. Her 2007 feature Mogari no mori (The Mourning Forest) screens there on Wednesday, July 2 at 6:30 pm and Monday, July 7 at 6:30 pm; on the same program is Kawase’s 2006 documentary Tarachime. In addition, Japan Society has scheduled two programs of Kawase’s earlier documentaries: the first program screens on Thursday, July 3 at 6:15 pm and Saturday, July 12 at 3:30 pm; the second screens on Thursday, July 3 at 8 pm and Saturday, July 12 at 5:30 pm. Mogari no mori is the Kawase feature I like the least – I’m more enthusiastic about Sharasojyu (Shara) (2003) and Moe no suzaku (Suzaku) (1998) – but her short films are very hard to see, and my guess is that the dividing line between her fiction and documentary work is fuzzy. There’s a paragraph about Mogari no mori in my 2007 Toronto piece for Senses of Cinema.

- The Tatsuya Nakadai retro at Film Forum contains two titles that I’ve been planning my life around ever since I saw the schedule. The biggie is the great Mikio Naruse’s 1957 Arakure (Untamed), which has a very good reputation, and which I didn’t think I’d ever get to see with subtitles. The other title is somewhat less promising, but still a must: Shiro Toyoda’s 1969 Jigokuhen (Portrait of Hell). Toyoda, a major director who is particularly good with actors, seems to have a spotty track record in his later part of his career, and this subject matter doesn’t sound as if it’s up his alley. But he followed Jigokuhen with the wonderful Kokotsu no hito (The Twilight Years) (1973), so I have hope.

- BAM is showing Jacques Nolot’s excellent Avant que j’oublie (Before I Forget) on Sunday, June 29 at 4:30 and 9:15 pm as part of its Directors’ Fortnight series. The film will then have its theatrical premiere at the IFC Center on July 18. See that 2007 Toronto wrapup for a brief review.

- NYC film buffs no doubt already have their sights on John Ford’s underrated The Horse Soldiers, playing at the Walter Reade on Sunday, July 6 as part of a William Holden retrospective. But they might want to stick around for the other film playing that day, John Sturges’s Escape From Fort Bravo. If my memory serves, it’s a worthwhile Western with nice hard-edged 1.33:1 compositions. Sturges directed a few other good films in the 50s and 60s, but this is my favorite. It screens at 3:30 and 8 pm, and The Horse Soldiers at 1 and 5:30 pm.

- I’m hoping to poke around a bit in the Walter Reade’s upcoming Slovenian film series: the former Yugoslav republics harbored a number of good filmmakers about whom we know little. The only film in the series that I can recommend in advance is Janez Berger’s 1999 V leru (Idle Running), a smart comedy about indolent bohemian youth. It screens on Sunday, July 20 at 6:45 pm and Monday, July 21 at 3:30 pm.

Wednesday, June 25, 2008

La Notte di San Lorenzo: Film or Theater?

I recently revisited La Notte di San Lorenzo (Night of the Shooting Stars), which is probably Paolo and Vittorio Taviani’s most celebrated film. It’s certainly one of their best, but it’s not a lonely eminence: the Tavianis, little talked about today, have made artistically daring and successful films throughout their long career, though they didn’t draw much international attention until 1977’s Padre Padrone, and then fell off the critical radar after 1987’s Good Morning, Babylon.

The first shot of La Notte di San Lorenzo is an artificially lit view of a domestic interior, dominated by a window that opens onto a painting of the night sky. Under a voiceover, the camera tracks into the window; at the end of the voiceover, a fake meteor streaks across the fake sky, and the title of the movie is suddenly printed on screen, synchronized with a music cue. As I watched, I thought to myself: this already feels completely like a Taviani Brothers film, and we’ve barely even seen any photography. The surprise of the title text, unleashed on the heels of the meteor and amplified with music, was enough to inscribe the Tavianis’ signature. The Taviani experience is a series of dramatic coups that do not grow from story, but rather disrupt it to create a direct communication from the filmmakers to the audience.

After watching ten minutes of the movie, I came to the conclusion that the Tavianis are really theater directors! Not an insult, to my mind…but theirs is not a very pure form of cinema.

Here’s an example. Fairly early in the film, the gentle patriarch Galvano (Omero Antonutti) stands on a crate in a shelter and announces to the gathered townspeople that he is going to flee the German-occupied village by night, inviting everyone to join him. The scene is done in a single camera setup: a low-angle of Galvano, isolated in the frame. Near the end of the speech, a dog in the room barks, and a shadow passes over Galvano’s face; he interpolates into the set of rules he is laying down, "And no dogs. They make noise." The Tavianis choose to keep the focus on the man’s pain rather than his message, on his gentleness rather than his leadership qualities: he adds, with a sad little smile, "I hadn’t thought it through."

We see in this moving scene many of the Tavianis’ human qualities: their exclusive interest in the personal view of large events, their swoops into subjectivity, their tendency to show the unexpected and the contradictory sides of people, their willingness to court the ridiculous. If, however, we consider the scene from a formal perspective, everything exciting and distinctive in it – Galvano’s isolation, the unexpected bark of the dog that changes his demeanor, the odd accumulation of sorrow at the end of the speech – is a coup de théâtre, a sudden, surprising gesture that changes the scene’s emotive qualities.

Imagine the same scene staged for the theater. Galvano stands alone on his crate, illuminated against a dark background. All other actors deliver their dialogue off stage; the dog is a sound effect. After Galvano falters and says, "I hadn’t thought it through," the lights fade and the scene ends.

My opinion is that we lose nothing in passing from the cinematic to the theatrical version. Every emotion, every surprise, is preserved in the translation. The use of space and the realism of the photographic record do not seem to be important to the scene’s effect.

Is it cinema? Yes and no, I suppose. Consider another powerful scene: after the exodus from the village, the townspeople camp on a hillside and wait to hear the explosions that will destroy their homes. A young woman who has previously expressed indifference to the loss of her childhood house is suddenly overtaken with sadness: she wonders aloud how she could possibly have wished for the destruction of her past. The Tavianis plunge into her thoughts with a fast tracking shot through the imagined house, ending on a presumed childhood memory: the girl, as a child, dances on a table in the living room with her family cheering her. Two more childhood memories appear: the girl sits on a sofa in the house with a young man; then, she stands in front of a bedroom mirror in her nightdress, pulling it up and staring at her own sex. After this daring (and typical for the Tavianis) psychic journey, the camera returns to the present.

In a sense, this example is not qualitatively different from the earlier scene: its power is due to a sudden and dramatic juxtaposition of different perspectives, a creative bravado that I would say is theatrical in essence. The movie images have beauty and kinesis, but their impact is dramatic, not textural. With some effort, we can imagine an expensive theater production in which a rotating stage brings the girl’s memories before our eyes: once again the film and theater implementations of the idea would be comparable in their emotional effect. But the film version looks better and is less labored.

Some scenes in the film could never be staged in a theater, and yet have elements in common with the above examples. For instance: as the villagers huddle in the shelter, a teenaged girl goes to a dark, abandoned room to urinate. The Tavianis cut from a long shot of the girl to closeups of a number of young boys who have apparently followed her: they watch avidly, and one of them masturbates. A closeup of the girl at the end of the sequence reveals that she is aware of the voyeurs and not displeased. The scene is too dependent upon silence and closeups to be called theatrical; and yet it is predicated on a series of coups, surprising revelations. Like the earlier scenes cited, it plays nearly as well in the imagination as in the moment of watching it.

If the Tavianis are really theater directors in sheep’s clothing, if their style is indeed an exploration of the cinema’s ability to express the theatrical impulse in new ways, this seems to me a perfectly worthy and productive endeavor. And tagging them with the label “theater” is certainly not the last word in describing their complicated, audacious artistic personality.

In addition to La Notte di San Lorenzo, I’d nominate Il Prato (The Meadow) (1979), Kaos (1984), and Le Affinità elettive (Elective Affinities) (1996) as the Tavianis’ peak achievements. But they’ve turned out impressive work at least as early as 1973’s Allonsanfan and as late as 2001’s Resurrezione (Resurrection).

The first shot of La Notte di San Lorenzo is an artificially lit view of a domestic interior, dominated by a window that opens onto a painting of the night sky. Under a voiceover, the camera tracks into the window; at the end of the voiceover, a fake meteor streaks across the fake sky, and the title of the movie is suddenly printed on screen, synchronized with a music cue. As I watched, I thought to myself: this already feels completely like a Taviani Brothers film, and we’ve barely even seen any photography. The surprise of the title text, unleashed on the heels of the meteor and amplified with music, was enough to inscribe the Tavianis’ signature. The Taviani experience is a series of dramatic coups that do not grow from story, but rather disrupt it to create a direct communication from the filmmakers to the audience.

After watching ten minutes of the movie, I came to the conclusion that the Tavianis are really theater directors! Not an insult, to my mind…but theirs is not a very pure form of cinema.

Here’s an example. Fairly early in the film, the gentle patriarch Galvano (Omero Antonutti) stands on a crate in a shelter and announces to the gathered townspeople that he is going to flee the German-occupied village by night, inviting everyone to join him. The scene is done in a single camera setup: a low-angle of Galvano, isolated in the frame. Near the end of the speech, a dog in the room barks, and a shadow passes over Galvano’s face; he interpolates into the set of rules he is laying down, "And no dogs. They make noise." The Tavianis choose to keep the focus on the man’s pain rather than his message, on his gentleness rather than his leadership qualities: he adds, with a sad little smile, "I hadn’t thought it through."

We see in this moving scene many of the Tavianis’ human qualities: their exclusive interest in the personal view of large events, their swoops into subjectivity, their tendency to show the unexpected and the contradictory sides of people, their willingness to court the ridiculous. If, however, we consider the scene from a formal perspective, everything exciting and distinctive in it – Galvano’s isolation, the unexpected bark of the dog that changes his demeanor, the odd accumulation of sorrow at the end of the speech – is a coup de théâtre, a sudden, surprising gesture that changes the scene’s emotive qualities.

Imagine the same scene staged for the theater. Galvano stands alone on his crate, illuminated against a dark background. All other actors deliver their dialogue off stage; the dog is a sound effect. After Galvano falters and says, "I hadn’t thought it through," the lights fade and the scene ends.

My opinion is that we lose nothing in passing from the cinematic to the theatrical version. Every emotion, every surprise, is preserved in the translation. The use of space and the realism of the photographic record do not seem to be important to the scene’s effect.

Is it cinema? Yes and no, I suppose. Consider another powerful scene: after the exodus from the village, the townspeople camp on a hillside and wait to hear the explosions that will destroy their homes. A young woman who has previously expressed indifference to the loss of her childhood house is suddenly overtaken with sadness: she wonders aloud how she could possibly have wished for the destruction of her past. The Tavianis plunge into her thoughts with a fast tracking shot through the imagined house, ending on a presumed childhood memory: the girl, as a child, dances on a table in the living room with her family cheering her. Two more childhood memories appear: the girl sits on a sofa in the house with a young man; then, she stands in front of a bedroom mirror in her nightdress, pulling it up and staring at her own sex. After this daring (and typical for the Tavianis) psychic journey, the camera returns to the present.

In a sense, this example is not qualitatively different from the earlier scene: its power is due to a sudden and dramatic juxtaposition of different perspectives, a creative bravado that I would say is theatrical in essence. The movie images have beauty and kinesis, but their impact is dramatic, not textural. With some effort, we can imagine an expensive theater production in which a rotating stage brings the girl’s memories before our eyes: once again the film and theater implementations of the idea would be comparable in their emotional effect. But the film version looks better and is less labored.

Some scenes in the film could never be staged in a theater, and yet have elements in common with the above examples. For instance: as the villagers huddle in the shelter, a teenaged girl goes to a dark, abandoned room to urinate. The Tavianis cut from a long shot of the girl to closeups of a number of young boys who have apparently followed her: they watch avidly, and one of them masturbates. A closeup of the girl at the end of the sequence reveals that she is aware of the voyeurs and not displeased. The scene is too dependent upon silence and closeups to be called theatrical; and yet it is predicated on a series of coups, surprising revelations. Like the earlier scenes cited, it plays nearly as well in the imagination as in the moment of watching it.

If the Tavianis are really theater directors in sheep’s clothing, if their style is indeed an exploration of the cinema’s ability to express the theatrical impulse in new ways, this seems to me a perfectly worthy and productive endeavor. And tagging them with the label “theater” is certainly not the last word in describing their complicated, audacious artistic personality.

In addition to La Notte di San Lorenzo, I’d nominate Il Prato (The Meadow) (1979), Kaos (1984), and Le Affinità elettive (Elective Affinities) (1996) as the Tavianis’ peak achievements. But they’ve turned out impressive work at least as early as 1973’s Allonsanfan and as late as 2001’s Resurrezione (Resurrection).

Friday, June 20, 2008

The Last Mistress: IFC Center, Starting June 27, 2008

Catherine Breillat's most recent movie, curiously titled The Last Mistress in English (its French title, Une vieille maîtresse, would probably be best translated as "an ex-mistress"), opens at the IFC Center on Friday, June 27. I think it's Breillat's best work since Fat Girl. Here's what I wrote about it for my 2007 Toronto piece in Senses of Cinema:

"Catherine Breillat’s Une vieille maîtresse was reasonably well-received at Cannes, but not well enough for my taste: typed as a niche provocatrice, Breillat is never granted centre stage in the world film arena, even with her critically successful projects. An adaptation of a 19th-century novel by Jules-Amédée Barbey d'Aurevilly, Une vieille maîtresse steps back from the grandiloquent philosophising of Romance (1999) and Anatomie de l'enfer (2004) and picks up the more multivalent discourse of earlier Breillat films like Parfait amour! (1996) and 36 fillette (1988). Of course, Breillat would not choose source material that did not challenge our conception of what a period film is supposed to be. At times, the movie seems to be about the attempt of a disreputable playboy (Fu'ad Ait Aattou) to find love and respectability with a young bride (Roxane Mesquida) and her surprisingly sympathetic grandmother (Claude Sarraute); more substantially, it depicts the long-term, intimate but unstable relationship between the playboy and a temperamental Spanish courtesan (Asia Argento); and, in passing, it documents society’s effort to understand and assimilate these difficult citizens. Breillat changes narrative gears several times, forcing us to plunge into an uncomfortable intimacy with the characters after an emotionally distant first act, and then letting our hard-won identification die away in a final section whose bleak ellipses reminded me of Bresson’s Lancelot du Lac (1974). Wrestling with the iconography and the mores of two separated centuries, Breillat throws out unexpected character and social observations like a Roman candle. Her vision of cruelty and empathy operating hand in hand in human nature gives her enormous freedom to inflect dramatic conventions, and she passes back and forth with assurance across the invisible barrier that separates sexuality from the rest of our lives."

"Catherine Breillat’s Une vieille maîtresse was reasonably well-received at Cannes, but not well enough for my taste: typed as a niche provocatrice, Breillat is never granted centre stage in the world film arena, even with her critically successful projects. An adaptation of a 19th-century novel by Jules-Amédée Barbey d'Aurevilly, Une vieille maîtresse steps back from the grandiloquent philosophising of Romance (1999) and Anatomie de l'enfer (2004) and picks up the more multivalent discourse of earlier Breillat films like Parfait amour! (1996) and 36 fillette (1988). Of course, Breillat would not choose source material that did not challenge our conception of what a period film is supposed to be. At times, the movie seems to be about the attempt of a disreputable playboy (Fu'ad Ait Aattou) to find love and respectability with a young bride (Roxane Mesquida) and her surprisingly sympathetic grandmother (Claude Sarraute); more substantially, it depicts the long-term, intimate but unstable relationship between the playboy and a temperamental Spanish courtesan (Asia Argento); and, in passing, it documents society’s effort to understand and assimilate these difficult citizens. Breillat changes narrative gears several times, forcing us to plunge into an uncomfortable intimacy with the characters after an emotionally distant first act, and then letting our hard-won identification die away in a final section whose bleak ellipses reminded me of Bresson’s Lancelot du Lac (1974). Wrestling with the iconography and the mores of two separated centuries, Breillat throws out unexpected character and social observations like a Roman candle. Her vision of cruelty and empathy operating hand in hand in human nature gives her enormous freedom to inflect dramatic conventions, and she passes back and forth with assurance across the invisible barrier that separates sexuality from the rest of our lives."

Wednesday, June 18, 2008

Happiness: IFC Center, June 23 and 28, 2008

One of my favorite films at last year's Toronto Film Festival, Hur Jin-ho's Happiness, screens at the IFC Center on Monday, June 23 at 2 pm and Saturday, June 28 at 5:20 pm as part of this year's New York Asian Film Festival. In my Toronto wrapup for Senses of Cinema, I wrote:

"My favorite Toronto premiere was the South Korean film Happiness, a jump up in quality from the previous work of the talented Hur Jin-ho (Palwolui Christmas [Christmas in August, 1998]; Bomnaleun ganda [One Fine Spring Day, 2001]). The story, about the love between a barely recovered playboy alcoholic (Hwang Jeong-min) and a fellow clinic patient with an incurable lung disease (Lim Su-jeong), is tinged with the sentimentality favoured by Korean melodramas. After only a few minutes, however, it becomes clear that Hur has achieved a quiet virtuosity in the rhythm and alternation of scenes, playing intelligently with the balance of intimacy and solitude, hope and despair, self-preserving and self-destructive impulses. Scenes are connected with unemphatic jump cuts that often end the action before its expected point of rest. The narrative is fatalistic on the large scale, but individual moments play with our expectations of how the emotional payload will be delivered, finding not only a calm that is not native to melodrama, but also an existential anguish that exceeds the requirements of the tearjerker. Beneath the emotive surface of Happiness, its melodrama is inflected with stoical detachment, right up to the beautiful desolation of the final crane shot.

"Happiness is a particularly nice surprise after Hur’s last film Oechul [April Snow, 2005], which seemed to show him being absorbed by the mainstream."

I'm also looking forward to two as-yet-unseen films by the excellent Ryuichi Hiroki (Vibrator, It's Only Talk) at the Asian Film Festival. Love on Sunday screens on Thursday, June 26 at 1 pm and on Sunday, June 29 at 1 pm; Love on Sunday 2: Last Words screens on Sunday, June 29 at 3 pm and on Wednesday, July 2 at 12:30 pm. All screenings of the Hiroki films are at the IFC Center.

"My favorite Toronto premiere was the South Korean film Happiness, a jump up in quality from the previous work of the talented Hur Jin-ho (Palwolui Christmas [Christmas in August, 1998]; Bomnaleun ganda [One Fine Spring Day, 2001]). The story, about the love between a barely recovered playboy alcoholic (Hwang Jeong-min) and a fellow clinic patient with an incurable lung disease (Lim Su-jeong), is tinged with the sentimentality favoured by Korean melodramas. After only a few minutes, however, it becomes clear that Hur has achieved a quiet virtuosity in the rhythm and alternation of scenes, playing intelligently with the balance of intimacy and solitude, hope and despair, self-preserving and self-destructive impulses. Scenes are connected with unemphatic jump cuts that often end the action before its expected point of rest. The narrative is fatalistic on the large scale, but individual moments play with our expectations of how the emotional payload will be delivered, finding not only a calm that is not native to melodrama, but also an existential anguish that exceeds the requirements of the tearjerker. Beneath the emotive surface of Happiness, its melodrama is inflected with stoical detachment, right up to the beautiful desolation of the final crane shot.

"Happiness is a particularly nice surprise after Hur’s last film Oechul [April Snow, 2005], which seemed to show him being absorbed by the mainstream."

I'm also looking forward to two as-yet-unseen films by the excellent Ryuichi Hiroki (Vibrator, It's Only Talk) at the Asian Film Festival. Love on Sunday screens on Thursday, June 26 at 1 pm and on Sunday, June 29 at 1 pm; Love on Sunday 2: Last Words screens on Sunday, June 29 at 3 pm and on Wednesday, July 2 at 12:30 pm. All screenings of the Hiroki films are at the IFC Center.

Tuesday, June 17, 2008

Possible Cancellation: Sait-on jamais....

As some of you know, Monday's screening of Vadim's Sait-on jamais... at MOMA was cancelled. The print was held up in customs and may or may not arrive in time for the Wednesday, June 18 screening; if it does, another screening will be added on Sunday, June 22 at 4 pm. Call the MOMA film box office (212 408 6663) to confirm the screenings.

Tuesday, June 10, 2008

Hatari!

The late Stuart Byron once wrote that even John Simon would understand the greatness of Hatari! were he forced to see it ten times. And, after my fifth viewing on Saturday night, I must say that I’m starting to come around to the film's considerable charms.

In a way, Hatari! throws up more obstacles for the Hawksian than for the lay viewer. Hawks’ penchant for recycling familiar dialogue and situations from his previous films starts to take on a ritualized, automatic quality at this point in his career. And the careful interweaving of events that was so impressive in Rio Bravo has given way in the space of one film to the most naked, barely motivated setups, as if Hawks no longer cared a whit about hiding behind the curtain or pretending that events are motivated by forces within the film universe.

Maybe I’ve just gotten used to this stuff, maybe it doesn't bother me so much at this point in my life, I don’t know. Anyway, I come here to praise Hatari!, not to bury it. What struck me most forcibly on this viewing is that, in place of the genre mechanisms that he formerly used as backdrop and jumping-off point, Hawks riffs off of a downright Bazinian conflation of fiction and documentary. Hawks had often revealed in the past his interest in process, in taking a bit of extra screen time to show how things work. (The night before my Hatari! screening, I saw the less distinguished Land of the Pharoahs, the main point of interest of which is watching Hawks and art director Alexandre Trauner practically build a real pyramid over the course of the movie.) But never before or after would Hawks devote so much effort to documenting a real activity – capturing wild animals – or suggesting that the actors playing the hunters were actually performing the job on screen. The characters who climb into specially designed land vehicles and head out on the plains of Tanganyika in search of game are doing exactly the same things as the film crew. Even the most credulous viewer will grasp that Hatari! is its own making-of documentary, a film about the fun of being an actor sent to Africa to camp out and chase animals.

John Wayne’s character, Sean Mercer (maybe Hawks and his writers were thinking of Sean Thornton, Wayne’s character in The Quiet Man – in El Dorado, Hawks would give Wayne the name Cole Thornton) swings toward the harsh side of Wayne’s familiar Hawksian persona. Is this because Wayne could not hide his irascible nature under the duress of wrestling rhinos to the ground? It looks like cinema-vérité when Wayne shoves Valentin de Vargas away during a particularly arduous capture, saying “We don’t need help here.” In any case, this edge of cruelty carries over to Wayne’s inhibited romance with Elsa Martinelli: one notably humiliating verbal skirmish, in front of a group of hunters, leaves Martinelli crestfallen. In reaction to Wayne’s less socialized behavior, the pressure that the group places on him to consummate the romance is correspondingly more direct and angry than in other Hawks films: not since Red River has Wayne come in for such contempt from his Hawksian cohort.

Martinelli, an appealing actress who plays her character, Dallas, a little more daft and wide-eyed than most Hawks heroines, also follows an atypical Hawksian character arc. Dallas is probably closest in conception to Jean Arthur’s Bonnie Lee in Only Angels Have Wings, in that she is largely marginalized by the neglect of the male protagonist, and can assert herself only through the self-defeating gesture of departing in tears. But something interesting happens to this Hawksian archetype in Hatari!: she finds an identity of her own, as a surrogate mother to animals. Biology asserts itself in a way that is unusual for Hawks: not only does Martinelli exhibit a maternal instinct rarely depicted in his films, but she also descends the food chain and joins the animal kingdom. Falling back on her own resources as romance disappoints her, she is absorbed into nature in the course of her maternal duties, covered in mud, water, paint, oblivious to human interaction. And, just as strangely, her transformation increases her appeal to her hesitant lover and to the group in general. In one of the film’s most memorable scenes, Martinelli gives her baby elephants a bath in a nearby lake while Wayne secretly follows with his gun to protect her, looking on with obvious admiration. Hawks does not seem uncomfortable with this exaggeration of traditional sex roles, though his career as a whole more often illustrates his pleasure in men and women crossing the gender divide.

One of the best scenes in Hatari! (which is constructed in an unusually modular fashion – it would not have been hard to relocate or excise scenes in the editing room) is a peculiar variation on a bit of blocking that Hawks used two decades earlier. After his capture of 500 monkeys using a rocket and a fishnet, Red Buttons’ Pockets haunts the compound’s common room, drunk and maudlin, asking the other hunters to tell him the story of his triumph over and over again. Wayne and Hardy Kruger are absorbed in a card game, but know that Buttons has earned the right to disturb their recreation, and so do their best to humor him while they play, describing the majestic rise of the rocket as if reading him a bedtime story. I flashed on the completely different scene in His Girl Friday in which the reporters in the news room alternately ignore Molly Malone and taunt her with throwaway wisecracks while they play cards. In both cases, the card players are confronted with a larger-than-life character: Buttons and Molly Malone are out of a different and more expansive movie, emoting theatrically and gesticulating wildly. And in both cases, the card players react with swallowed-up naturalism, muttering about the game under their breath, clearly establishing themselves on a behavioral level that is quieter, faster, more unstressed than the one occupied by their stylized interlocutors. Starting with dissimilar character dynamics and story objectives, Hawks exhibits the same instinct to create a gap between levels of abstraction, and to exploit that gap to heighten the illusion of realism.

In a way, Hatari! throws up more obstacles for the Hawksian than for the lay viewer. Hawks’ penchant for recycling familiar dialogue and situations from his previous films starts to take on a ritualized, automatic quality at this point in his career. And the careful interweaving of events that was so impressive in Rio Bravo has given way in the space of one film to the most naked, barely motivated setups, as if Hawks no longer cared a whit about hiding behind the curtain or pretending that events are motivated by forces within the film universe.

Maybe I’ve just gotten used to this stuff, maybe it doesn't bother me so much at this point in my life, I don’t know. Anyway, I come here to praise Hatari!, not to bury it. What struck me most forcibly on this viewing is that, in place of the genre mechanisms that he formerly used as backdrop and jumping-off point, Hawks riffs off of a downright Bazinian conflation of fiction and documentary. Hawks had often revealed in the past his interest in process, in taking a bit of extra screen time to show how things work. (The night before my Hatari! screening, I saw the less distinguished Land of the Pharoahs, the main point of interest of which is watching Hawks and art director Alexandre Trauner practically build a real pyramid over the course of the movie.) But never before or after would Hawks devote so much effort to documenting a real activity – capturing wild animals – or suggesting that the actors playing the hunters were actually performing the job on screen. The characters who climb into specially designed land vehicles and head out on the plains of Tanganyika in search of game are doing exactly the same things as the film crew. Even the most credulous viewer will grasp that Hatari! is its own making-of documentary, a film about the fun of being an actor sent to Africa to camp out and chase animals.

John Wayne’s character, Sean Mercer (maybe Hawks and his writers were thinking of Sean Thornton, Wayne’s character in The Quiet Man – in El Dorado, Hawks would give Wayne the name Cole Thornton) swings toward the harsh side of Wayne’s familiar Hawksian persona. Is this because Wayne could not hide his irascible nature under the duress of wrestling rhinos to the ground? It looks like cinema-vérité when Wayne shoves Valentin de Vargas away during a particularly arduous capture, saying “We don’t need help here.” In any case, this edge of cruelty carries over to Wayne’s inhibited romance with Elsa Martinelli: one notably humiliating verbal skirmish, in front of a group of hunters, leaves Martinelli crestfallen. In reaction to Wayne’s less socialized behavior, the pressure that the group places on him to consummate the romance is correspondingly more direct and angry than in other Hawks films: not since Red River has Wayne come in for such contempt from his Hawksian cohort.

Martinelli, an appealing actress who plays her character, Dallas, a little more daft and wide-eyed than most Hawks heroines, also follows an atypical Hawksian character arc. Dallas is probably closest in conception to Jean Arthur’s Bonnie Lee in Only Angels Have Wings, in that she is largely marginalized by the neglect of the male protagonist, and can assert herself only through the self-defeating gesture of departing in tears. But something interesting happens to this Hawksian archetype in Hatari!: she finds an identity of her own, as a surrogate mother to animals. Biology asserts itself in a way that is unusual for Hawks: not only does Martinelli exhibit a maternal instinct rarely depicted in his films, but she also descends the food chain and joins the animal kingdom. Falling back on her own resources as romance disappoints her, she is absorbed into nature in the course of her maternal duties, covered in mud, water, paint, oblivious to human interaction. And, just as strangely, her transformation increases her appeal to her hesitant lover and to the group in general. In one of the film’s most memorable scenes, Martinelli gives her baby elephants a bath in a nearby lake while Wayne secretly follows with his gun to protect her, looking on with obvious admiration. Hawks does not seem uncomfortable with this exaggeration of traditional sex roles, though his career as a whole more often illustrates his pleasure in men and women crossing the gender divide.

One of the best scenes in Hatari! (which is constructed in an unusually modular fashion – it would not have been hard to relocate or excise scenes in the editing room) is a peculiar variation on a bit of blocking that Hawks used two decades earlier. After his capture of 500 monkeys using a rocket and a fishnet, Red Buttons’ Pockets haunts the compound’s common room, drunk and maudlin, asking the other hunters to tell him the story of his triumph over and over again. Wayne and Hardy Kruger are absorbed in a card game, but know that Buttons has earned the right to disturb their recreation, and so do their best to humor him while they play, describing the majestic rise of the rocket as if reading him a bedtime story. I flashed on the completely different scene in His Girl Friday in which the reporters in the news room alternately ignore Molly Malone and taunt her with throwaway wisecracks while they play cards. In both cases, the card players are confronted with a larger-than-life character: Buttons and Molly Malone are out of a different and more expansive movie, emoting theatrically and gesticulating wildly. And in both cases, the card players react with swallowed-up naturalism, muttering about the game under their breath, clearly establishing themselves on a behavioral level that is quieter, faster, more unstressed than the one occupied by their stylized interlocutors. Starting with dissimilar character dynamics and story objectives, Hawks exhibits the same instinct to create a gap between levels of abstraction, and to exploit that gap to heighten the illusion of realism.

Thursday, June 5, 2008

Late Hawks: Anthology Film Archives, June 4 through 15, 2008

Anthology Film Archives' much-anticipated Late Hawks series began yesterday, and continues through June 15. An article I wrote on the series is up at the new Moving Image Source site.

Tuesday, June 3, 2008

Nakahira vs. Vadim, and a Bit About Composition in General

I accidentally created an interesting double bill when I attended back-to-back screenings at MOMA of Yasushi Nakahira’s 1956 Kurutta kajitsu (Crazed Fruit, aka Juvenile Passion) and Roger Vadim’s 1959 Les Liaisons dangereuses. Both Nakahira and Vadim were championed in the mid to late 50s by the Cahiers du Cinema critics, who used them as sticks to beat the mainstream French cinema for its stiffness and orthodoxy. And both directors enjoyed only a brief period of critical favor: Nakahira never made another splash in the West, and Vadim quickly alienated the affections of Cahiers and its followers.

(The historically appropriate pairing of these films isn’t pure coincidence. The Cahiers critics of the time seemed to take a special interest in films about youth: possibly because the subject matter encouraged a freer directorial style; possibly also because the Cahiers writers were young themselves and trying to foment a revolution. The Nakahira and Vadim films were both part of MOMA’s Jazz Score series – and jazz music and youth subjects went hand in hand in films of the 50s.)

Truffaut, whose review of Kurutta kajitsu was compiled and translated into English in My Life and My Films, made the connection between Nakahira and Vadim:

"In short, you will have guessed, Ishihara (Editor’s note: screenwriter Shintarô Ishihara, the central literary figure of Japan’s 50s “taiyozoku” youth culture) is called in Poland the Marek Hlasko of Japan, and in France the Sagan/Vadim/Buffet of Japan. The second is certainly warranted, since it seems clear that Juvenile Passion was influenced by And God Created Woman (Et Dieu...créa la femme), which played in Japan at the same time it was released in France.

"As in Vadim’s first film, we are shown two brothers who are successively the lovers of a young woman unhappily married to an American. I find the Japanese film superior to its French model from every point of view: script, direction, acting, spirit."

The Cahiers writers would always define Vadim by Et Dieu...créa la femme, which fascinated them upon its 1956 release, and seemed to them to point the way toward a new and freer cinema. It’s not the Vadim film that appeals to me most. Still, I think Vadim’s now-depressed reputation deserves a lift, and I certainly thought he got the better of Nakahira in that evening’s faceoff at MOMA.

One of the appeals of Kurutta kajitsu is that the characters are rebellious enough to confound certain genre expectations. The enigmatic female lead (Mie Kitahara, seen in NYC recently in Tomu Uchida’s memorable Jibun no ana no nakade [A Hole of My Own Making]) plays a triple game as wife, innocent, and slut, but is not typed as duplicitous: the film suggests that her desires are sincere in each compartment of her life. And the older brother (Yûjirô Ishihara) betrays his sibling, not from malevolence or weakness, but from impulsiveness wedded to a reckless existentialism. Director Nakahira makes unusual and vigorous attempts to convey the subjective experiences of the characters, using point-of-view shots and focusing on small-scale events to associate the boys’ lives with immediacy and sensation.

Still, Nakahira strikes me as stronger on big concepts than on moment-by-moment direction. Too often his performers fall back on conventional signposting within each scene, even when the characters don’t reduce to simple concepts. (Chabrol corrected this shortcoming in 1959’s Les Cousins, which could be seen as a loose reworking of Kurutta kajitsu.) And I don’t find Nakahira a visually expressive director: he manages a number of attractive shots, mostly in exteriors, but produces unremarkable results with basic tasks like cutting between characters or laying out simple action.

The simple scenes in Les Liaisons dangereuses are exactly where Vadim establishes his talent. His compositions and camera movements have great natural beauty, and also preserve a balance between subjectivity and an objective, environmental perspective. The now-familiar source material (I haven’t read Laclos’ novel, but I feel as if I have after seeing at least four adaptations of it) opens an intriguing gap between the malevolence of the protagonists and their more conventional sentimental aspirations, and Vadim and his writer Roger Vailland are intuitive enough to enhance the emotional gravity that accompanies the characters’ nasty gamesmanship. The best example of this approach is the stunning scene in which Valmont (Gérard Philipe) presses his courtship of the chaste Marianne (Annette Vadim) while they walk amid snowy mountains at a winter resort. Valmont’s seduction strategy, described in voiceover, is to tell Marianne the truth about his life of depravity; and so the scene plays with a built-in dual perspective, according to which Valmont makes both a calculating power play and a naked confession to a woman who is already more than just a victim to him. Vadim plays the scene for maximum solemnity, letting Valmont’s words resonate in the majestic spaces that shift behind the characters, and keeping his camera a little low and far enough away from the couple that their figures never completely eclipse the elemental environment.

Throughout the film, Vadim’s innate seriousness makes it possible for him to give the cruelty of the subject matter its full weight, neither softening it (cf. the Forman/Carrière and Kumble versions of the story) nor implicating himself in it (cf. the Frears/Hampton version). This is not to deny a certain number of missteps, mostly near the ending, possibly attributable to internal or external censorship. One can see Vadim as divided between a fruitful iconoclasm and a more conventional or conformist tendency. (If film criticism has tended to regard Vadim as the cinema’s answer to Hugh Hefner…well, Hefner too is half revolutionary and half conformist, and his career declined in the same precipitous fashion.)

Before I insert images into this blog for the first time, I’m going to make a tentative attempt to generalize some of the above comments about composition. When I watch a movie and think, “These images are intrinsically beautiful – this director really knows how to compose,” and then try to analyze the visual style, I often conclude that the compositions are balanced between two functions: showing the figure in the foreground, and showing the world. The balance is always managed in such a way that the shot can still function in the mind of the viewer as a depiction of the foreground figure; and yet the room or landscape is presented with some spatial integrity.

And every time I watch a movie and think, “These images are dull and conventional,” I conclude upon further analysis that the compositions are framed as if they are trying to present only one object, or one idea, and that the image reduces in my mind to a concept. Closeups are composed to show the person and not much else; longer shots are far enough back that the relation of the object or person to the surroundings seems to motivate the composition. I don’t necessarily think that shots that fit this description are a liability, but they miss out on intrinsic beauty, because they suggest a concept too strongly. In some cases shots like these gain value from being part of a larger artistic structure.

I was first put onto this train of thought when I attended another circumstantial double bill at MOMA of Mankiewicz’s House of Strangers and Fregonese’s Black Tuesday. I felt as the films had utterly different visual agendas: it seemed to me that every shot in the Mankiewicz film had a single concept behind it, and could be translated into words without loss; and that every shot in the Fregonese film was a picture of the world, with its complexity preserved.

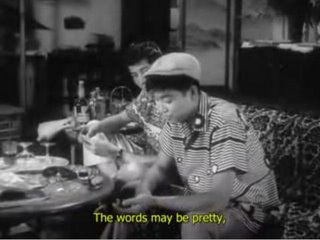

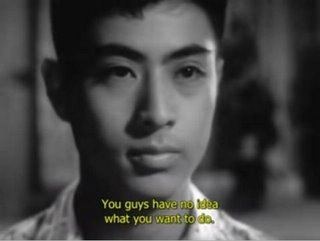

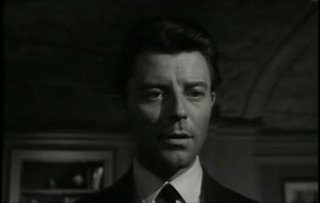

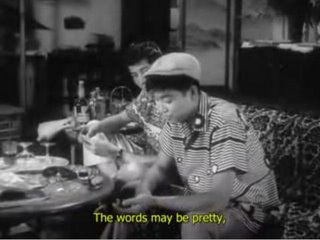

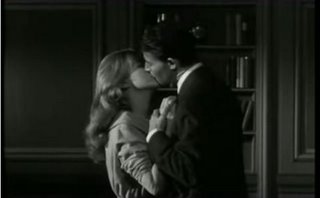

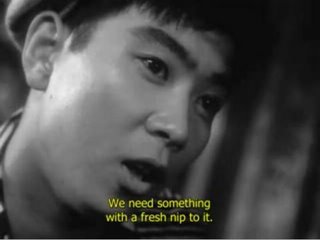

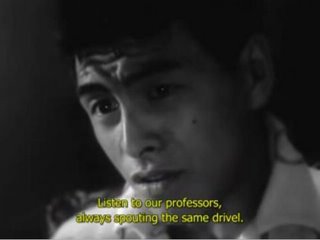

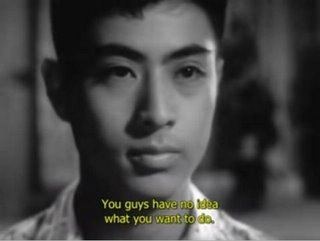

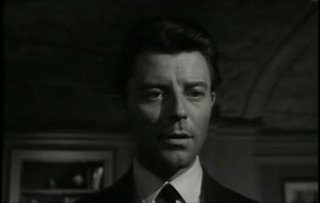

I don’t have DVDs of Kurutta kajitsu or Les Liaisons dangereuses, so I’ll compare still images from the films that I found on YouTube. From the very limited selection of clips available, I chose two fairly unremarkable interior scenes: a teen party from Kurutta kajitsu in which the representatives of reckless youth state their credo; and the culmination of Valmont’s attempt to seduce Marianne in Les Liaisons dangereuses. The scenes have different emotional trajectories (not to mention different aspect ratios) and therefore don’t compare perfectly, but they do give a sense of Nakahira and Vadim’s compositional tendencies.

Let’s compare two-shots first. The Nakahira scene is heavy on closeups, but it contains a few two-shots:

The lack of compositional tension in the shots can partly be chalked up to the emotionally neutral content of the scene: none of the characters in these two-shots have a strong personal relationship to each other. Nonetheless, the layout of these shots has a cerebral quality to me: the two figures in the frame are just large enough that the frame seems to be about them and little else. The background is visible in the shots, and even has some visual appeal in the second shot; but for me the size of the people in the frame sends a signal that the background isn’t motivating the placement of the camera.

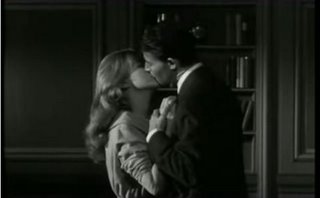

The Vadim clip is longer, so it provides more varied examples. And the emotional tension between Valmont and Marianne is at a high point, which to some extent mandates additional diagonal tension. Here are a few two-shots in this scene that are relatively free of diagonal tension, and therefore compare better to Nakahira’s two-shots:

Allowing for the wider aspect ratio that Vadim uses, and also for Vadim’s use of deep focus, these shots aren’t wildly different from Nakahira’s. (The deep focus is, of course, not irrelevant to this discussion: it’s certainly an invitation to experience the characters as part of the environment. I don’t know much about Vadim’s director of photography here, Marcel Grignon. He seems to have had a long career in the European film industry, but I recognize only a few of his credits, principally Clement’s Paris brûle-t-il? and Borowczyk’s La Bête. He worked with Vadim once again, in 1963 on Le Vice et la vertu.) I perceive a greater tendency in Vadim to arrange his actors to create a sort of human terrain, a landscape with perspective and contour.

Other two-shots in the scene make greater use of distance and diagonality:

Here we see an interest in the environment that doesn’t have a parallel in the Nakahira scene. The deep focus in these shots is clearly part of a plan to photograph the texture and the space in the room, while configuring the actors in dramatic opposition to each other. There is very little in the story that draws our attention to the setting: Vadim could easily have conceived the scene as an abstract personal confrontation, but he seems to think naturally in terms of topography.

Finally, a few closer two-shots drive home the idea of actors as terrain:

There is not much in the way of background in these shots, but the people are invested with spatial qualities of their own. I often thought of mid-period Antonioni when watching Les Liaisons dangereuses; it didn’t occur to me until afterwards that the film was released nine months before L’avventura, the film that popularized Antonioni’s wide-screen compositional style.

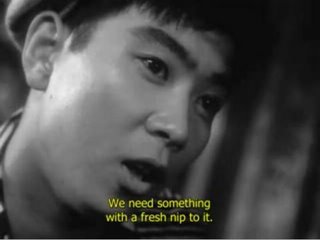

Now for one-shots. The scene I’ve chosen from Kurutta kajitsu centers on a Soviet-inspired montage sequence that cuts among a number of tight closeups, usually with tilted compositions:

The composition that isn’t tilted is the closeup of the straight-arrow brother, whereas the tilted closeups go to the “taiyozoku.” This correspondence between composition and characterization is way too blatant to have any resonance for me.

The scene contains a few one-shots that are more conventional:

Again, Nakahira frames simply, with no apparent intention other than to show the actor. There is some visual tension in the background with the wooden railing; the direct framing of the boy again discourages me from registering him in his environmental context.

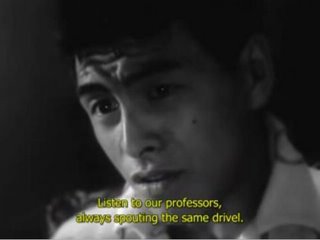

Vadim’s simplest one-shots aren’t much more complicated:

Most of the added environmental presence can be chalked up to the wider aspect ratio and the use of deep focus. Often, however, Vadim clearly shows a desire to situate the characters amid their decor, even with the limited amount of screen acreage available to show background in one-shots:

The wider aspect ratio gives Vadim greater opportunity to place actors off-center and highlight the décor, Antonioni-style.

As with the two-shots cited earlier, some of the one-shots strongly suggest the topographical qualities of the bodies of the actors:

At one point, Vadim creates an off-center composition around Marianne, then moves Valmont into the frame for a more massed, topographical effect. Practically the same framing serves both halves of the shot, which suggests that Vadim’s compositions are friendly to the absence of the actors as well as their presence.

I haven’t seen Vadim’s 1957 Sait-on jamais... (No Sun in Venice), but it's often cited as one of Vadim's best (Godard reviewed it favorably in Cahiers), and it screens at MOMA in the Jazz Score series on Monday, June 16 at 6 pm and Wednesday, June 18 at 6:45 pm.

(The historically appropriate pairing of these films isn’t pure coincidence. The Cahiers critics of the time seemed to take a special interest in films about youth: possibly because the subject matter encouraged a freer directorial style; possibly also because the Cahiers writers were young themselves and trying to foment a revolution. The Nakahira and Vadim films were both part of MOMA’s Jazz Score series – and jazz music and youth subjects went hand in hand in films of the 50s.)

Truffaut, whose review of Kurutta kajitsu was compiled and translated into English in My Life and My Films, made the connection between Nakahira and Vadim:

"In short, you will have guessed, Ishihara (Editor’s note: screenwriter Shintarô Ishihara, the central literary figure of Japan’s 50s “taiyozoku” youth culture) is called in Poland the Marek Hlasko of Japan, and in France the Sagan/Vadim/Buffet of Japan. The second is certainly warranted, since it seems clear that Juvenile Passion was influenced by And God Created Woman (Et Dieu...créa la femme), which played in Japan at the same time it was released in France.

"As in Vadim’s first film, we are shown two brothers who are successively the lovers of a young woman unhappily married to an American. I find the Japanese film superior to its French model from every point of view: script, direction, acting, spirit."

The Cahiers writers would always define Vadim by Et Dieu...créa la femme, which fascinated them upon its 1956 release, and seemed to them to point the way toward a new and freer cinema. It’s not the Vadim film that appeals to me most. Still, I think Vadim’s now-depressed reputation deserves a lift, and I certainly thought he got the better of Nakahira in that evening’s faceoff at MOMA.

One of the appeals of Kurutta kajitsu is that the characters are rebellious enough to confound certain genre expectations. The enigmatic female lead (Mie Kitahara, seen in NYC recently in Tomu Uchida’s memorable Jibun no ana no nakade [A Hole of My Own Making]) plays a triple game as wife, innocent, and slut, but is not typed as duplicitous: the film suggests that her desires are sincere in each compartment of her life. And the older brother (Yûjirô Ishihara) betrays his sibling, not from malevolence or weakness, but from impulsiveness wedded to a reckless existentialism. Director Nakahira makes unusual and vigorous attempts to convey the subjective experiences of the characters, using point-of-view shots and focusing on small-scale events to associate the boys’ lives with immediacy and sensation.

Still, Nakahira strikes me as stronger on big concepts than on moment-by-moment direction. Too often his performers fall back on conventional signposting within each scene, even when the characters don’t reduce to simple concepts. (Chabrol corrected this shortcoming in 1959’s Les Cousins, which could be seen as a loose reworking of Kurutta kajitsu.) And I don’t find Nakahira a visually expressive director: he manages a number of attractive shots, mostly in exteriors, but produces unremarkable results with basic tasks like cutting between characters or laying out simple action.

The simple scenes in Les Liaisons dangereuses are exactly where Vadim establishes his talent. His compositions and camera movements have great natural beauty, and also preserve a balance between subjectivity and an objective, environmental perspective. The now-familiar source material (I haven’t read Laclos’ novel, but I feel as if I have after seeing at least four adaptations of it) opens an intriguing gap between the malevolence of the protagonists and their more conventional sentimental aspirations, and Vadim and his writer Roger Vailland are intuitive enough to enhance the emotional gravity that accompanies the characters’ nasty gamesmanship. The best example of this approach is the stunning scene in which Valmont (Gérard Philipe) presses his courtship of the chaste Marianne (Annette Vadim) while they walk amid snowy mountains at a winter resort. Valmont’s seduction strategy, described in voiceover, is to tell Marianne the truth about his life of depravity; and so the scene plays with a built-in dual perspective, according to which Valmont makes both a calculating power play and a naked confession to a woman who is already more than just a victim to him. Vadim plays the scene for maximum solemnity, letting Valmont’s words resonate in the majestic spaces that shift behind the characters, and keeping his camera a little low and far enough away from the couple that their figures never completely eclipse the elemental environment.

Throughout the film, Vadim’s innate seriousness makes it possible for him to give the cruelty of the subject matter its full weight, neither softening it (cf. the Forman/Carrière and Kumble versions of the story) nor implicating himself in it (cf. the Frears/Hampton version). This is not to deny a certain number of missteps, mostly near the ending, possibly attributable to internal or external censorship. One can see Vadim as divided between a fruitful iconoclasm and a more conventional or conformist tendency. (If film criticism has tended to regard Vadim as the cinema’s answer to Hugh Hefner…well, Hefner too is half revolutionary and half conformist, and his career declined in the same precipitous fashion.)

Before I insert images into this blog for the first time, I’m going to make a tentative attempt to generalize some of the above comments about composition. When I watch a movie and think, “These images are intrinsically beautiful – this director really knows how to compose,” and then try to analyze the visual style, I often conclude that the compositions are balanced between two functions: showing the figure in the foreground, and showing the world. The balance is always managed in such a way that the shot can still function in the mind of the viewer as a depiction of the foreground figure; and yet the room or landscape is presented with some spatial integrity.

And every time I watch a movie and think, “These images are dull and conventional,” I conclude upon further analysis that the compositions are framed as if they are trying to present only one object, or one idea, and that the image reduces in my mind to a concept. Closeups are composed to show the person and not much else; longer shots are far enough back that the relation of the object or person to the surroundings seems to motivate the composition. I don’t necessarily think that shots that fit this description are a liability, but they miss out on intrinsic beauty, because they suggest a concept too strongly. In some cases shots like these gain value from being part of a larger artistic structure.

I was first put onto this train of thought when I attended another circumstantial double bill at MOMA of Mankiewicz’s House of Strangers and Fregonese’s Black Tuesday. I felt as the films had utterly different visual agendas: it seemed to me that every shot in the Mankiewicz film had a single concept behind it, and could be translated into words without loss; and that every shot in the Fregonese film was a picture of the world, with its complexity preserved.

I don’t have DVDs of Kurutta kajitsu or Les Liaisons dangereuses, so I’ll compare still images from the films that I found on YouTube. From the very limited selection of clips available, I chose two fairly unremarkable interior scenes: a teen party from Kurutta kajitsu in which the representatives of reckless youth state their credo; and the culmination of Valmont’s attempt to seduce Marianne in Les Liaisons dangereuses. The scenes have different emotional trajectories (not to mention different aspect ratios) and therefore don’t compare perfectly, but they do give a sense of Nakahira and Vadim’s compositional tendencies.

Let’s compare two-shots first. The Nakahira scene is heavy on closeups, but it contains a few two-shots:

The lack of compositional tension in the shots can partly be chalked up to the emotionally neutral content of the scene: none of the characters in these two-shots have a strong personal relationship to each other. Nonetheless, the layout of these shots has a cerebral quality to me: the two figures in the frame are just large enough that the frame seems to be about them and little else. The background is visible in the shots, and even has some visual appeal in the second shot; but for me the size of the people in the frame sends a signal that the background isn’t motivating the placement of the camera.

The Vadim clip is longer, so it provides more varied examples. And the emotional tension between Valmont and Marianne is at a high point, which to some extent mandates additional diagonal tension. Here are a few two-shots in this scene that are relatively free of diagonal tension, and therefore compare better to Nakahira’s two-shots:

Allowing for the wider aspect ratio that Vadim uses, and also for Vadim’s use of deep focus, these shots aren’t wildly different from Nakahira’s. (The deep focus is, of course, not irrelevant to this discussion: it’s certainly an invitation to experience the characters as part of the environment. I don’t know much about Vadim’s director of photography here, Marcel Grignon. He seems to have had a long career in the European film industry, but I recognize only a few of his credits, principally Clement’s Paris brûle-t-il? and Borowczyk’s La Bête. He worked with Vadim once again, in 1963 on Le Vice et la vertu.) I perceive a greater tendency in Vadim to arrange his actors to create a sort of human terrain, a landscape with perspective and contour.

Other two-shots in the scene make greater use of distance and diagonality:

Here we see an interest in the environment that doesn’t have a parallel in the Nakahira scene. The deep focus in these shots is clearly part of a plan to photograph the texture and the space in the room, while configuring the actors in dramatic opposition to each other. There is very little in the story that draws our attention to the setting: Vadim could easily have conceived the scene as an abstract personal confrontation, but he seems to think naturally in terms of topography.

Finally, a few closer two-shots drive home the idea of actors as terrain:

There is not much in the way of background in these shots, but the people are invested with spatial qualities of their own. I often thought of mid-period Antonioni when watching Les Liaisons dangereuses; it didn’t occur to me until afterwards that the film was released nine months before L’avventura, the film that popularized Antonioni’s wide-screen compositional style.

Now for one-shots. The scene I’ve chosen from Kurutta kajitsu centers on a Soviet-inspired montage sequence that cuts among a number of tight closeups, usually with tilted compositions:

The composition that isn’t tilted is the closeup of the straight-arrow brother, whereas the tilted closeups go to the “taiyozoku.” This correspondence between composition and characterization is way too blatant to have any resonance for me.

The scene contains a few one-shots that are more conventional:

Again, Nakahira frames simply, with no apparent intention other than to show the actor. There is some visual tension in the background with the wooden railing; the direct framing of the boy again discourages me from registering him in his environmental context.

Vadim’s simplest one-shots aren’t much more complicated:

Most of the added environmental presence can be chalked up to the wider aspect ratio and the use of deep focus. Often, however, Vadim clearly shows a desire to situate the characters amid their decor, even with the limited amount of screen acreage available to show background in one-shots:

The wider aspect ratio gives Vadim greater opportunity to place actors off-center and highlight the décor, Antonioni-style.

As with the two-shots cited earlier, some of the one-shots strongly suggest the topographical qualities of the bodies of the actors:

At one point, Vadim creates an off-center composition around Marianne, then moves Valmont into the frame for a more massed, topographical effect. Practically the same framing serves both halves of the shot, which suggests that Vadim’s compositions are friendly to the absence of the actors as well as their presence.

I haven’t seen Vadim’s 1957 Sait-on jamais... (No Sun in Venice), but it's often cited as one of Vadim's best (Godard reviewed it favorably in Cahiers), and it screens at MOMA in the Jazz Score series on Monday, June 16 at 6 pm and Wednesday, June 18 at 6:45 pm.

Darling

A few weeks ago I took a chance on Swedish director Johan Kling's Darling when it screened at Scandinavia House, because the trailer looked interesting. I loved the movie, and wrote a short review that's up at the Auteurs' Notebook. As far as I can tell, Darling is available only on Region 2 DVD with no English subtitles - but I wouldn't be surprised if Kling has his day soon.